For years, law enforcement agencies across the United States have attempted to keep details of a dragnet cellphone surveillance tool under wraps. But their efforts have fallen short time and time again thanks to intrepid journalists and civil liberties groups who have successfully filed public records requests seeking information about these spy devices.

One of the most-recent requests of this type comes from the American Civili Liberties Union and the New York Civil Liberties Union who for two years have fought federal immigration agencies to learn more about how their law enforcement officers use so-called Stingray devices to catch targets and gather evidence.

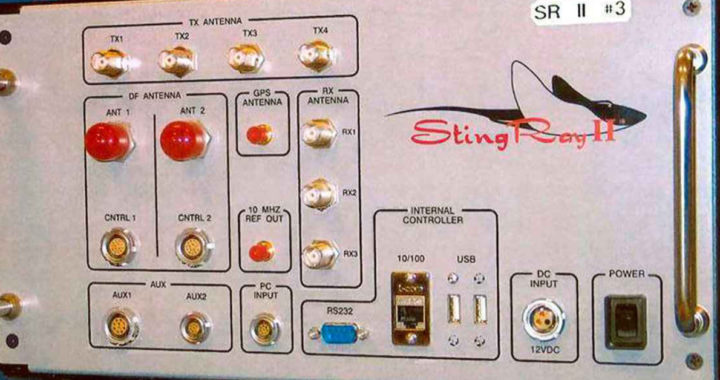

Sold by the Florida-based Harris Corporation, a “Stingray” is a cell site simulator device that tricks phones to connect to it instead of a legitimate communications tower. When deployed, Stingrays force all phones in a given area — sometimes as large as a few city blocks — to re-route phone signals to it. Using attached computers, law enforcement officers are able to obtain phone data like call and text message logs and geographic location.

While officers may be using Stingrays to capture criminal suspects, their design means ordinary, often innocent individuals also have their phone data swooped up by the devices. Few law enforcement agencies have acknowledged using the devices, and even fewer have offered details about how they purge data of innocent individuals who are not the targets of their investigations.

The shroud of secrecy around Stingrays and similar devices runs so deep that prosecutors have been known to drop criminal cases to keep police use of these devices hidden from public knowledge. Some criminal cases have later been re-opened after judges and defense attorneys learned that “confidential sources” used in investigations were actually Stingrays.

Law enforcement agencies say they’ve been directed by federal officials to keep their purchase and use of Stingrays and other devices a secret because of non-disclosure agreements forged between those agencies, the federal government and Harris Corporation. But judges have routinely sided with the ACLU and other organizations who file records requests for information about Stingrays, and details about the devices have trickled out for years.

One of the most-egregious details learned from public records requests is how state, county and local law enforcement agencies are able to obtain the devices. Records show departments routinely request Department of Homeland Security grants to purchase Stingrays and accessories, which can total in the thousands of dollars.

Grant applications say police departments, including some in California, need to obtain the devices for use in anti-terrorism investigations. But documents obtained by local media outlets show the devices are often used in ordinary criminal investigations with no nexus to terrorism or homeland security matters.

In 2017, the Detroit News published an article describing how immigration agents there were using Stingrays to track down undocumented immigrants following a crackdown issued by President Donald Trump. That report was the basis for a series of public records requests filed by the ACLU seeking information on how often Immigrations and Custom Enforcement (ICE), Border Patrol and other federal immigration agencies were using Stingrays and for what purpose.

After waiting two years, the ACLU filed a lawsuit against ICE and their sister agencies, the Customs and Border Patrol (CPB). The lawsuit worked, and earlier this year, those federal agencies started handing over hundreds of documents (PDF 1, PDF 2) related to their use of Stingrays and other devices.

According to the ACLU, the documents show ICE spent hundreds of thousands of dollars securing Stingrays and upgrading to newer hardware called Crossbow that allows immigration agents to track 3G and 4G LTE smartphones of targets. The documents show ICE had used either a Stingray, Crossbow or some other kind of cellphone transmitter simulator more than 400 times between 2017 and 2019.

One of the most alarming revelations in the document is that law enforcement agencies have known since at least 2016 that ordinary phone users can deploy so-called “IMSI catchers” that simulate the very data collection activity that Stingrays and Crossbows possess. While federal officials suggested deploying anti-IMSI catchers in the wild, they worked hard to keep knowledge about this vulnerability a secret, even though it had the ability to threaten the privacy and security of ordinary phone users.

Worse, while officials in other countries have measured whether use of Stingrays or Crossbows can impair a person’s ability to make emergency phone calls (they can, studies conducted by these governments show), federal agencies have so far failed to carry out their own similar testing to see if using these phone surveillance tools could interfere with 9-1-1- calls.

“There can’t be accountability without transparency,” the ACLU said in a statement issued earlier this week. “The release of these records — albeit with redactions — provides some helpful insights into what was previously an extremely secretive surveillance practice. … That’s good news, but concerns remain.”

Those concerns include how ICE uses these surveillance tools in ordinary immigration cases while telling the public that it doesn’t and CPB’s failure to turn over documents under the ACLU’s FOIA (the CPB says it has no responsive records, but the ACLU said this is unlikely because documents already made public revealed CPB had spent $2.5 million to obtain 33 cellphone transmitter simulator devices).

“We’re demanding the court order CBP to explain how it conducted its prior searches for records responsive to our FOIA request and to conduct a new search for responsive records,” the ACLU said. “The use of powerful, surreptitious surveillance equipment is concerning in any context. But when agencies such as ICE and CBP, with a long history of abusive practices, evade requests for information and then obfuscate provided information, we should all be concerned.”